Understanding Academic Paragraphs

In this article I construct some simple paragraph rules that will help you act today and become a better academic writer.

In this article, I construct some simple paragraph rules that will help you act today and become a better academic writer.

If you liken writing, to building a house - paragraphs would be the bricks. When crafting your writing they act as the key unit of composition. So, you may have gathered that the paragraph is one of the most important tools in your writing arsenal. Nonetheless, I have noticed that many people (also myself, before I made an effort to deliberately improve my academic writing) make some fundamental mistakes. Luckily, these mistakes can easily be avoided by following some simple rules. In implementing these rules into my academic own writing, I believe I have become a more proficient written communicator.

Before I dive in and define these rules, I want you to first consider that:

Academic writing can be framed as a specific genre of writing.

Distinguishing academic writing as a genre has proven an extremely useful improvement tool. It allowed me to learn the stylistic rules of the genre – differentiating it from other more common, often sensationalist, styles of writing. So, in this vein, let’s begin by exploring how to construct paragraphs by framing them in their respective genres.

Journalistic Writing

Primarily, in your day-to-day life (at least your online life), you’ll be exposed to different flavours of journalistic writing (e.g., news, blogs and advertising copy). The goal is to draw the readers in with attention-grabbing titles, images and headlines. You’ll often find that the paragraphs and sentences used are short and punchy - to quickly convey information. For instance, it is common to see single-sentence paragraphs:

As Australia prepares to begin the rollout of Covid-19 vaccines, state health departments, including SA Health and Queensland Health, were unable to post.

For formal forms of writing, the paragraphs are generally longer. Statements made within the paragraph need to be supported by evidence; as such, the length of the paragraph increases. Let's explore this idea by considering paragraphs in general, and then framing them more academically.

The Golden Rules of Paragraphs

Unlike much of the English language, academic paragraphs follow a very simple golden rule:

Each paragraph consists of a single idea.

A paragraph representing a single idea is a fundamental rule applicable to most writing genres. This idea is captured in a single sentence known as the topic sentence, usually at the start paragraph. If you are writing informally, the topic sentence can stand by itself. However, for more formal writing styles, a topic statement needs supporting evidence.

The Academic Paragraph

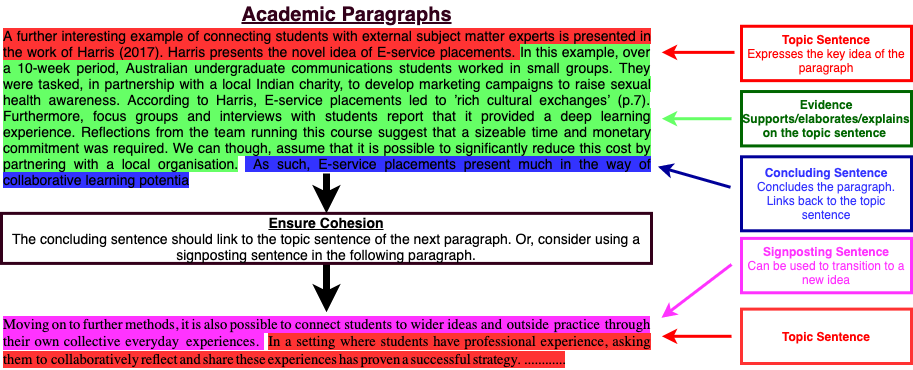

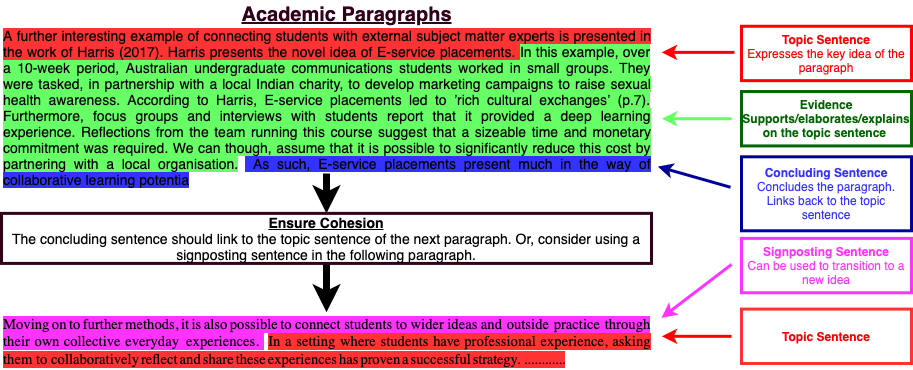

We’ve already established that a paragraph, as a minimum, should have a topic sentence. However, in academic writing it is generally not enough for a topic sentence to stand alone by itself - this is especially the case if the paragraph is important. Academic paragraphs should consist of three key parts:

- Topic sentence - expresses the key idea

- Evidence - Supports/elaborates/explains the topic sentence

- Concluding sentence - concludes the paragraph, should link back to the topic sentence

While each paragraph should present a stand-alone idea, there should be a logical flow between paragraphs. This is achieved through linking the concluding sentence to the topic sentence of the next paragraph; or, if the wider idea is transitioning, you can use a signposting sentence before the topic sentence.

A clear indicator that you are writing cohesive paragraphs is by reading the first signpost and topic sentence of each paragraph in isolation. If there is a clear flow you are achieving a very high level of writing.

The trick is to ensure cohesion, while at the same time ensuring that paragraphs can stand by themselves. As such, it would be quite rare to start off a new paragraph with words that are explicitly tied to a statement in the previous paragraph. Therefore, try and avoid starting a paragraph with linking words such as: however, therefore and on the other hand.

In summary, when you are crafting and editing your work, you’ll want to keep the three parts of the academic paragraph in mind (topic sentence, evidence and concluding sentence). We are using these ideas to scaffold and underpin with evidence a single idea.

Understanding the, seemingly humble paragraph, has probably had the greatest effect on the path to academic writing mediocrity.